1. Program architecture and flow

rsudp is laid out in a way that is standard for many continuous monitoring softwares, but which may be unfamiliar to some developers.

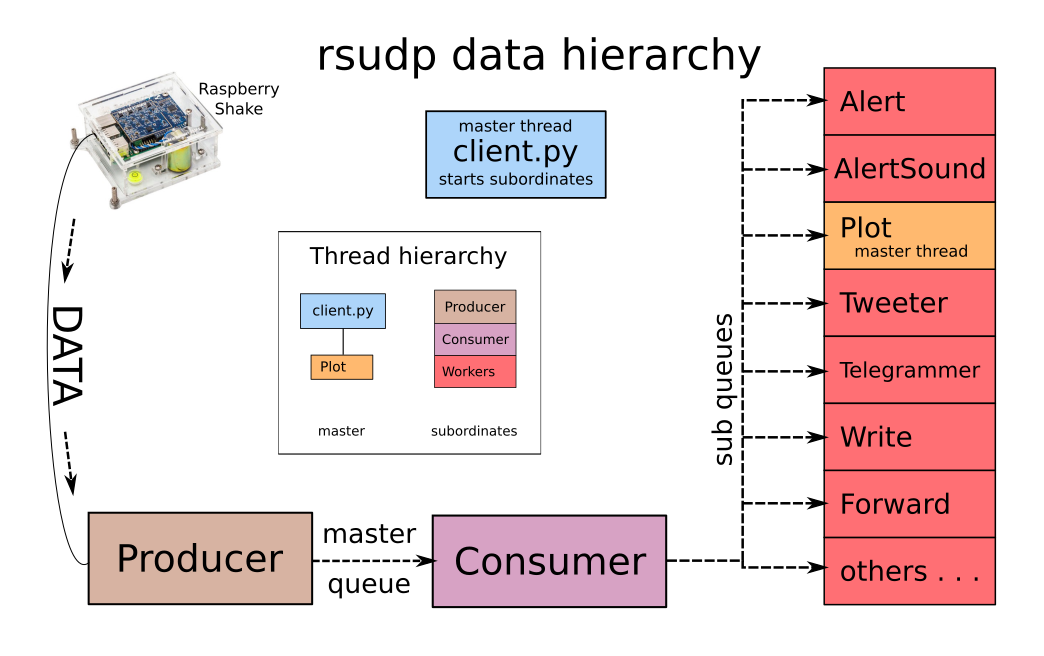

The program’s organization relies on two hierarchies: thread hierarchy and

data hierarchy. This allows the program to distribute data and messages

between different modules efficiently while maintaining programmatic

integrity required by rsudp’s dependencies (matplotlib.pyplot

objects, for example, can only be owned by the master thread).

Data and (inset) thread hierarchies for rsudp. This figure shows a flow chart of data as it makes its way through rsudp’s producer-consumer architecture, and eventually to the end-consumer processing the data. Thread hierarchies are shown in the inset chart. If you are looking to add a module to rsudp, it will be a worker class (red) and will receive data from the master consumer like the rest of the workers.

1.1. Thread layout

The program relies on the threading and queue modules

to spin up multiple threads which all receive and work with data

independently of one another.

First, the rsudp.client (the “main” or “parent” thread) gathers

and parses settings. The client then instantiates the relevant

threading.Thread objects and passes settings and queues to

them. Next, it starts each of these consumer threads as “child” threads,

then finally the producer, also as a child thread.

If the rsudp.c_plot.Plot thread is enabled, the program will

start that last, since plotting must be run as a loop controlled by the

main thread (rsudp.client) which can only be done once it has

started all of its child threads.

1.2. Producer-consumer message passing

Data is read off the port by the data producer

(rsudp.p_producer.Producer) and passed directly to the

(rsudp.c_consumer.Consumer) via a first-in first-out (FIFO)

queue object.

This master consumer then duplicates these messages and

passes them to each sub-consumer queue destination in a list. At the

other end of each of these queues is a sub-consumer module, denoted

with a c_ before its module name.

Sub-consumers read messages from their queues and process data in

their logic loops. Some build obspy.core.stream.Stream with

the data passed to them, while some ignore the data and watch for

status messages.

1.2.1. Message types

Added in version 0.4.3: the RESET message type was added.

Currently, the message types are as follows.

Message |

Format example |

|---|---|

data |

|

ALARM |

|

RESET |

|

IMGPATH |

|

TERM |

|

Note

The above message formats are Python bytes objects, not traditional strings. The difference between a bytes object and a string is outlined briefly here.

ALARM messages are sent by rsudp.p_producer.Producer

when it sees the rsudp.c_consumer.Alert.alarm flag set to

True. This can trigger all sorts of actions. For example, when the

rsudp.c_alertsound.AlertSound module is enabled and sees

this message, it uses ffmpeg or libav to play a sound. The social media

classes rsudp.c_tweet.Tweeter and

rsudp.c_telegram.Telegrammer both use this message to

instantly broadcast to their respective platforms.

RESET messages are sent by rsudp.p_producer.Producer

when it sees the rsudp.c_consumer.Alert.alarm flag set to

True. Similar to ALARM messages, consumers can be programmed for

an essentially infinite number of things upon seeing this message.

IMGPATH messages are placed on the master queue by the

rsudp.c_plot.Plot.savefig() function, if and when a screenshot

figure is saved to disk. This is currently only used by the social media

modules, rsudp.c_tweet.Tweeter and

rsudp.c_telegram.Telegrammer which then send the saved image

to their respective social media platforms’ APIs for broadcast.

TERM messages are the universal signal for rsudp to quit. They generally start at the Producer and are passed through the data hierarchy as normal data would.

1.3. Adding your own consumer modules

Adding consumer modules is easy in theory, when you understand the workings of rsudp’s layout. Using the existing modules’ code architecture is likely useful and should be encouraged, so feel free to follow along with what we have already laid out in the code base.

There are three main things that need to happen in order to add a consumer.

Create a new module, named

c_mymodule.py, in thersudpdirectory.Add a section to your settings file which will tell rsudp what settings to pass to your module.

Add code to

rsudp.client.run()to pass settings and a queue to your module, and start it.

And some optional things to do in case you plan on submitting a pull request:

Add documentation in the form of reStructuredText-formatted docstrings (see examples below)

Add testing capability to your module.

1.3.1. Sample consumer

Below is a sample consumer construction to modify for your own purposes.

It receives all queue messages (outlined in Producer-consumer message passing)

and can be made to do pretty much whatever you wish,

until it receives a TERM queue message.

This consumer is created from a

rsudp.raspberryshake.ConsumerThread object,

which in turn modifies the threading.Thread class.

import sys

from rsudp.raspberryshake import ConsumerThread

from rsudp import printM

class MyModule(ConsumerThread): # this means MyModule will be based on the ConsumerThread class

'''

Documentation of your new module class goes here.

Below is the format of two types of *param* string, which tell the

documentation parser to inform users that this object needs the user to

pass it a queue in order to work correctly.

The first string, for the ``q`` parameter, has the type as the

middle object and the caption after. The second one, ``thing1``

could either be a string or a boolean value,

so we move the type for it to its own row with the types listed after.

Sphinx, the documentation formatter, will be able to combine these into

one object describing the parameter.

:param queue.Queue q: queue of data and messages sent by :class:`rsudp.c_consumer.Consumer`

:param thing1: a passed parameter that's either a string or a boolean (True/False)

:type thing1: bool or str

'''

def __init__(self, q, thing1 # ... probably some more parameters to pass to the class

)

super().__init__()

self.sender = 'MyModule'

self.alive = True

self.queue = q

self.thing1 = thing1

# ... lots of other stuff to initialize your module

printM(self.thing1, sender=self.sender)

def getq(self):

'''

Reads data from the queue and returns the queue object.

Since this function returns something, it has return

strings (*rtype* stands for return type) so that the

user reading the documentation knows what they'll get

back if they call it.

:rtype: bytes

:return: The queue object.

'''

d = self.queue.get()

self.queue.task_done()

return d

def run(self):

'''

Documenting how my cool module runs!

Right now, its only function is to get and read queue messages

to see if one of them has the ``TERM`` message in it,

at which point it quits.

'''

printM('Starting.', sender=self.sender)

# some stuff to execute here at runtime before looping

while self.alive:

# main loop, do something until self.alive == False

d = self.getq()

if 'TERM' in str(d):

self.alive = False

# now exit

printM('Exiting.', sender=self.sender)

sys.exit()

1.3.2. Adding your module to the settings file

An example settings section is given here. As a reminder, each settings section except the last one is required to have a comma after its closing brace to conform to JSON standards. Here let’s assume this is not the last JSON section, so we include the comma:

"mymodule": {

"enabled": true,

"thing1": "first thing"},

1.3.3. Adding your module to client.py

Since all modules are started from the client’s rsudp.client.run()

function, you will need to add a section of code to the client to tell it

how to start your module.

An example based on the JSON section above is given here.

from c_mymodule import MyModule

# ... lots of other stuff in client.py

def run(settings, debug):

# ... setting up other modules

if settings['mymodule']['enabled']:

# first, gather settings

thing1 = settings['mymodule']['thing1']

# then, set up queue

q = mk_q()

# then, start a MyModule instance with the settings you got earlier

mymod = MyModule(q=q, thing1=thing1)

# now, pass this instance to the process list to be started below

mk_p(mymod)

# ...

# this part already exists, but just to show you where in sequence your code should be:

start()

# ...

1.3.4. Testing your module

Formal testing of new modules is easy in rsudp.

The rsudp.client.test() function is set to run any enabled

module by default. If the module is not enabled in the default

settings, you can add a line to the

rsudp.test.make_test_settings() that specifies

settings['your_module']['enabled'] = True

The second step is to add your test to the dictionary of tests in

rsudp.test, so that it gets reported. For example:

TEST = {

# other tests

# ...

'c_mytest': ['something I am testing for ', False],

'c_anotherone': ['some other thing I test ', False],

}

Each dictionary item is constructed as a two-item list, where the first item is the description string, and the second is the status of the test (False is failure and True is passing).

Then, in your module, you can import the test dictionary and modify the status of your tests like so:

from rsudp.raspberryshake import ConsumerThread

from rsudp.test import TEST

class MyModule(ConsumerThread):

def __init__(self, q # ...

)

super().__init__()

# ... stuff to initialize your module

if abc:

# this test occurs during initialization

TEST['c_mytest'][1] = True

def run(self):

# some stuff here also

if xyz:

# this test is done at runtime

TEST['c_anotherone'][1] = True

while self.alive:

# main loop, do something until self.alive == False

# or you receive the TERM message

# now exit

printM('Exiting.', self.sender)

sys.exit()

1.4. Suggesting features

As with other issues, if you have an idea for a feature addition but have questions about how to implement it, we encourage you to post to our forums at https://community.raspberryshake.org.

Thanks for supporting open source!